Modern Rinzai Comes From Hakuin - Pt. 1

We’ve been examining the origins of the Rinzai lineage of my teacher Jun Po Roshi. Our first blog started with Jun Po Roshi and we worked our way backwards to Hakuin. The second installment started with Nampo Shomyo, who traveled to China to receive the transmission from Xutang Zhiyi, a direct lineage holder of Linji Yixuan, or Master Rinzai. We skipped Hakuin Ekaku, who so deservedly requires several blogs devoted to his teachings.

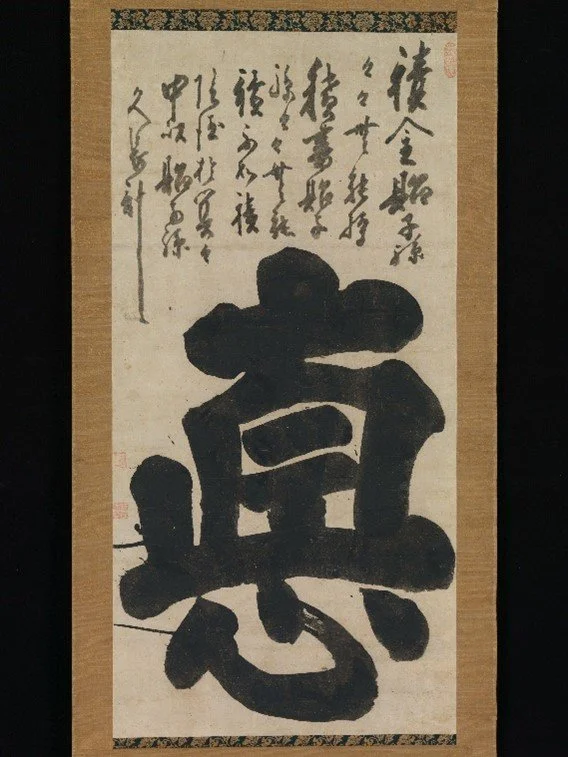

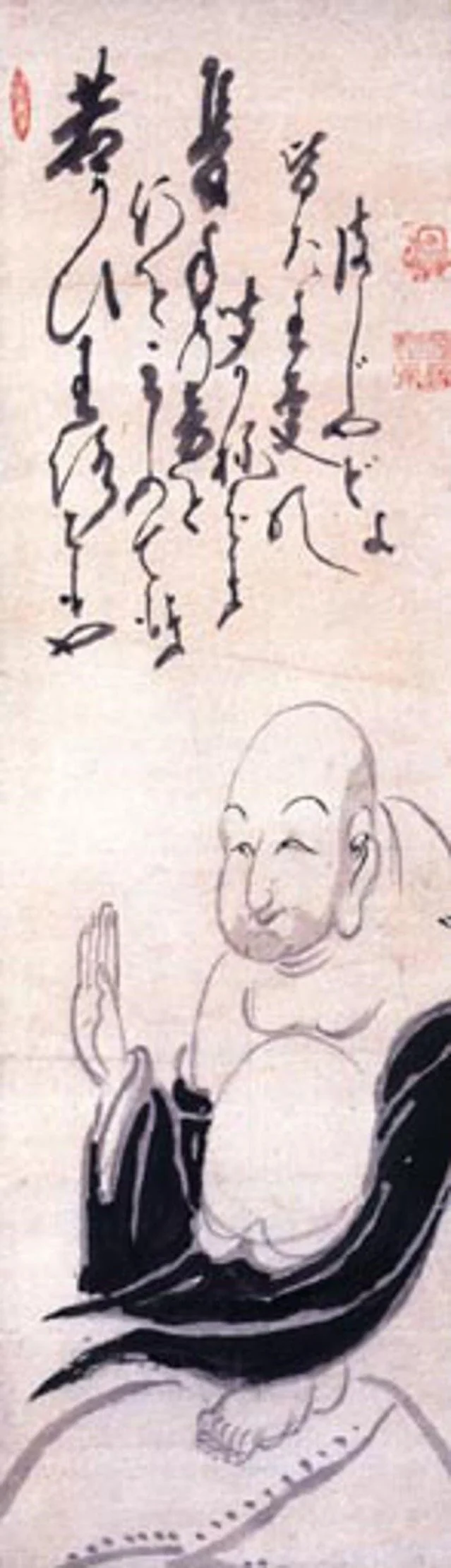

Hakuin Ekaku (1685 – 1769) is responsible for bringing Rinzai Zen back into fashion in the 18th century. All of the current forms of Rinzai Zen practiced in Japan, the United States and throughout the world can be traced back to Hakuin Zenji. Aside from his brilliant, innovative insight, several factors helped establish Hakuin’s prominent position. First, he wrote extensively, which is not so common for Zenmasters. Aside from Eihei Dogen, no other Zenmaster in Japanese Zen produced such an extensive library of literary works, including personal letters, an autobiography, talks, lectures, and a vast number of teishos (formal talks). He was an artist as well, with painting and calligraphy his medium of choice. While he did not make art to sell, he did create over 3500 works, many of which can be found in prominent museums throughout the world today. One does not need to be a Zen student to have come in contact with Hakuin the artist.

“Virtue” by Hakuin Ekaku

Hakuin’s writings are often challenging, particularly his teachings on Zen. In contrast to his artwork, which considers a broad range of public and private life in early 18th century Japan, Hakuin often writes about koans or classical teachings from the Chan era in China. He is most actively remembered for his Song of Zazen, which is regularly chanted in Rinzai temples before a teisho by a Roshi. In an effort to make sense of Hakuin’s work and impact, I will present four themes. This blog will consider the first two.

Hakuin’s Rinzai Zen practice requires working with koans, which he referred to as “poison words.” The Rinzai emphasis on koan practice is considered the most advanced and significant way to attain spiritual breakthrough (Kensho).

Initial awakening (Kensho) is not the end of the process, rather it is the beginning, and thus, Hakuin established the need for post-enlightenment training.

It is essential that one’s personal enlightenment experience be part of the legacy of Zen for future students, hence his commitment to the Bodhisattva Vow.

Hakuin devoted considerable energy denouncing other contemporary forms of Zen for their role in the decline of Zen.

Poison Words – The Use of Koans in Rinzai Zen

We have considerable information and knowledge about Hakuin’s life through his autobiography, Wild Ivy, and a detailed biography by his student Torei Enji. Hakuin was born and raised in Hara with the family name Nagasawa. His birth name was Iwajiro, meaning “boy of rock.” At age 14, he undertook formal study of Zen Buddhism with Sokin, a senior monk at nearby Shoin Monastery. He was ordained a year later by Abbot Tanrei Soden and was given the name Ekaku or “Wisdom Crane.” At nineteen, in search of a teacher, his journey involved travel throughout Japan. He studied with many teachers before he finally found Dokyo Etan, also known as Old Man of Shoju Rojin. Dokyo Etan had been trained by Abbot Shido Bunan of Tohoku Monastery. Etan promptly offered Ekaku the Mu koan, also known as Joshu’s koan.

Mu proved to be a challenge for young Ekaku. While going door to door begging for food, as was customary of monks, and while continuously attending to his koan, Ekaku was beaten by an old man. Falling to the ground unconscious, he was helped up by several passers-by. When he opened his eyes, he recognized he had solved the koan. Soon after, Dokyo Etan certified Ekaku’s enlightenment. This was in 1708. Hakuin was 23 years old.

Upon returning to Shoin–ji, Ekaku was installed as the abbot. He soon became Hakuin, Haku meaning “white” and in meaning “hiding,” thus, “Hiding-in-white.” He was then invited to be the Shuso – head monk - at Myoshin-ji monastery, the apex school for the Rinzai Lineage, founded by Daito Kakoushi with Kanzan Egen as the first abbot. When his term was over, Hakuin returned to Shoin-ji, a small monastery where he would pretty much remain for the rest of his life.

Hakuin’s teaching focused on the use of koans. He felt that Silent Illumination, the Soto practice of “just sitting,” was the downfall of Zen in Japan. He promoted an active approach to Zen practice favoring meditation in activity. His koan practice evolved out of teachings of Dahui Zonggao (1089 – 1163), who developed a technique for working with koans by using capping phrases, or hua-tou, which would allow the practitioner to continuously attend to the koan day and night, even when engaging in activity. Jun Po Roshi too developed a series of capping phrases for his Mondo Zen Facilitation. He called this dharana practice.

Hakuin’s fluidity with koans eventually formed into a koan curriculum, a series of koans that move through several phases as the student deepens their insight. This curriculum included primary texts, such as the Mumonkan and the Blue Cliff Record. This novel curriculum would be further refined by his student Gasan Jito (1727-1797) and Gasan’s primary heirs, Inzan Ien and Takuju Kosen. Our lineage, through Eido Shimano, comes directly from Takuju Kosen. Inzan Ien’s line would find its way to the west through Omori Sogen Roshi (1904-1994), who established the first Rinzai Monastery outside of Japan in 1972 in Hawaii.

Post-enlightenment Training

For much of Hakuin’s career, Joshu’s Mu koan was the entry point into the koan curriculum. However, in his later years, he shifted to a koan of his own making. “In order to attain kensho… you must first of all hear the sound of one hand. Nor must you be satisfied with hearing the sound, you must go on and put a stop to all sounds” (Norman Waddell’s introduction in Hakuin’s Precious Mirror Cave: A Zen Miscellany, pg. 62). I hear Jun Po Roshi’s “Can you listen without an opinion” as a modernization of Hakuin’s “sound of one hand.” But answering the koan was not the end, rather it was the beginning of koan training. “Even then you cannot relax your efforts - the deeper your enlightenment becomes, the greater the effort you must expend… [after passing the most difficult koans], you must read extensively in Buddhist and non-Buddhist literature, accumulate an inexhaustible store of Dharma assets, then devote your life exclusively to the endless practice of preaching the Dharma and guiding beings to liberation” (ibid p. 4-5). One can see how deeply Hakuin was committed to the literature of Buddhism, as well as the practice of ongoing koan study.

In later years, he wrote for a more lay audience. These works include The Tale of My Childhood and The Tale of Yukichi Takayam. In this latter book, Waddell sums up Hakuin’s teachings on the commitment to post-enlightenment training.

At first he taught using the Mu koan: then he erected a two-fold barrier of koans – the Sound of One Hand and Put a Stop to All Sounds. He called these barriers the “claw and fangs of the Dharma cave,” “divine, death-dealing amulets.” But even if an authentic Zen student - a patrician of secret depths - breaks past the double barrier, he still has ten thousand additional barriers, an endless thicket of impenetrable thorns and briars to pass through, not to mention one final, firmly-closed, tightly-locked gate. Once he has succeeded in passing through all these barriers one-by-one, he must arouse Bodhi-mind and devote his life to carrying out the great matter of post-satori practice.”

(Hakuin’s Precious Mirror Cave: A Zen Miscellany, pg. 5)

Hakuin demonstrates a commitment to lifelong learning, to personal accountability and to spreading the dharma. His writings reflect an extremely high level of scholarship, and his artwork reflects a commitment to reach out to audiences beyond the monks that filled his monastery. He was a lifelong learner himself, and his emphasis was on continued growth and development. Hakuin was an avid reader and a highly motivated, disciplined monk who demonstrated his commitment to awakening throughout his adult life. This passion drew hordes of monks and lay students to him as his reputation grew.

We’ll pick up the final two themes of Hakuin’s teachings the next blog, “Modern Rinzai Comes From Hakuin - Part 2.”