Deepening Our Understanding of Hakuin - Pt. 2

In this second part of my biography of Hakuin Ekaku, I take up his teaching on post-enlightenment training. I then discuss his ongoing tendency to dress down other practitioners of Zen who he felt were inferior. Finally, I take a brief look at Hakuin the artist, offering a very brief glance at the diversity of subjects he chose to paint.

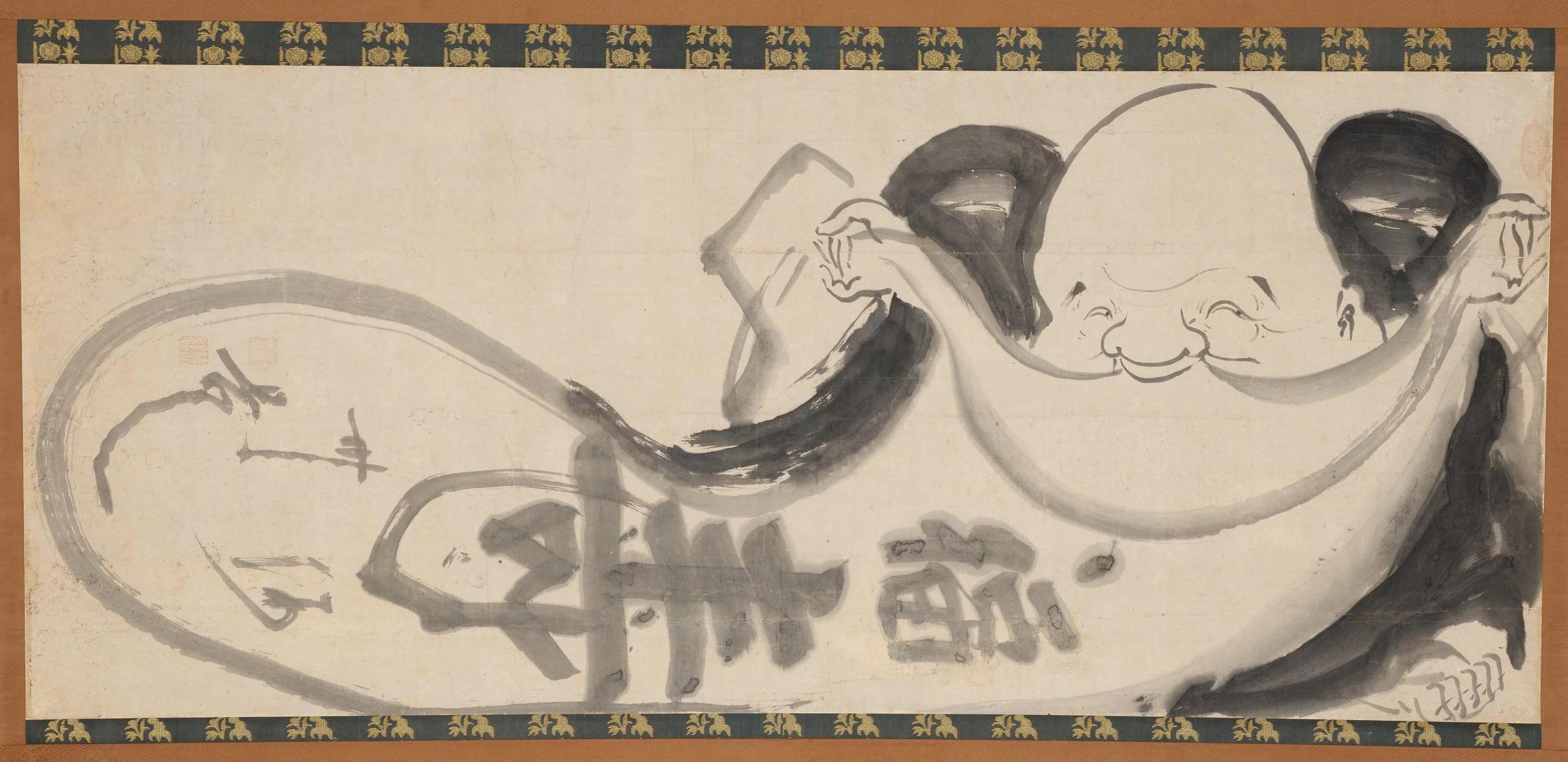

Akiba Sajakubo by Hakuin Ekaku

Hakuin’s commitment to serving the Dharma is best demonstrated by his extensive written teachings. Norman Waddell has gifted us with many excellent English translations. In Japanese, there is an eight-volume publication of the complete works of Hakuin. In English, one can find many texts including Wild Ivy—his autobiography—Hakuin on Kensho, Poison Blossoms from a Thicket of Thorn, The Essential Teachings of Hakuin, Hakuin’s Precious Mirror Cave, and Beating the Cloth Drum: Letters of Zen Master Hakuin. There are also several excellent collections of his art: The Religious Art of Zen Master Hakuin by Katsuhiro Yoshizawa and Norman Waddell; The Sound of One Hand: Paintings and Calligraphy of Zen Master Hakuin by Audrey Yoshiko Seo and Stephen Addiss; and Penetrating Laughter: Hakuin’s Zen & Art by Kazuaki Tanahashi. In this second blog on Hakuin Zenji, I will discuss Hakuin’s notion of post-enlightenment training, his ongoing and vocal criticism of other forms of Zen, and a brief look into Hakuin the artist.

Post-Enlightenment Training

While Hakuin’s Rinzai is most associated with kensho, or the initial experience of awakening, he was committed to ongoing training using koans as a means for deepening one’s insight and skillful means. This approach stood out in contrast to Soto practice of the time, which primarily attended to direct experience or silent illumination, known as shikantaza. A contemporary of Hakuin, Bankei Zenji taught of “the unborn,” which was essentially a silent illumination practice of shikantaza. For Hakuin, this was navel gazing. He taught that the mind must be trained through ongoing koan work, which is an active meditation practice that can be engaged in all the time, not just on a meditation cushion.

Rather than deepening development of the ever-present pure awareness through direct presencing, koan work engages the mind through narrative and mental effort. Victor Sogen Hori, a modern koan scholar, discusses the contradictions between the primary Chan perspective that Chan or Zen is beyond words, which is best exemplified by Bodhidharma’s seminal story of sitting facing a wall for nine years, versus koan practice, which is, in fact, a literary device that uses historical stories to cultivate a type of ongoing attention bringing about deeper and deeper states of insight. The use of stories, parables and literary devices was quite common in China throughout the ages, so it was no surprise that as Chan evolved in the Song dynasty—roughly the 10th-13th centuries. These koans, or public cases, became essential to many of the practices of Chan at that time.

The challenge for us now, as Hori points out, is that in context, many of these stories exist and reflect cultural perspectives that only make sense when offered in the appropriate cultural setting—Song Dynasty China. Thus, when we modern folks take up koans, the considerable amount of necessary cultural background required to understand and make one’s way through the koan curriculum is unavailable to us. That doesn’t mean that it can’t be done; it means that koan study is not just a meditation practice, it also includes vast amounts of study to allow for this deeper work to be done. Hakuin was pretty clear about this. His priests were trained to be lifelong learners, exemplifying the third of the Four Awakened Vows, which states, “However vast and difficult true teachings are, I vow to embody and master them all.”

Thus, it’s naïve to think that koan work is simply done with interior mental activity. Cultural and intellectual practices are also essential to the practice. Rinzai Zen developed strict protocols for how to participate in ceremony and practice. Hakuin’s koans turned into a set curriculum that students move through systematically. This emphasis on personal introspection and strict sangha roleplay means the deepening of compassion is left to develop on its own, rather than being a key part of practice and development. We can contrast this with other traditions that center practices intended to deepen compassion, such as Theravadin Metta meditations and Tonglen in Tibetan Vajrayana. With this in mind, it’s fair to say Hakuin’s Rinzai Zen emphasizes intellectual, mental and spiritual development over emotional development. It requires the practitioner to invest in long periods of koan introspection as well as extensive textual study, given that there is so much to learn about the cultural underpinnings of the practice. It’s no wonder Jun Po Roshi felt the need to add emotional koans to the curriculum. Emotional growth and development are pretty much bypassed in traditional Rinzai practice.

Hotei Opening His Sack - Hakuin Ekaku

Ongoing Criticism of Other Forms of Zen

This is best reflected in Hakuin’s ongoing and intense criticism of other forms of Zen. Let’s take a look at this with a quote:

What do I mean by “blind tortoise?” One of the current crop of sightless, irresponsible bungler-priests who regard the koan as nonessential, and the Zen interview as the master’s expedient means. While even such men are not totally devoid of understanding, they are clearly standing outside the gates, whence they peer fecklessly in, mouthing words like “Self-nature is naturally pure, the mind-source is deep as an ocean. There is no samsaric existence to cast aside, there is no nirvana to be sought. It is sheer and profound stillness, a transparent mass of boundless emptiness. It is here that is found the great treasure inherent in all people. How could anything be lacking?”

Ah, how plausible it sounds! All too plausible. Unfortunately, the words they speak do not possess even a shred of strength in practical applications. These people are snails. The moment anything approaches, they draw in their horns and come to a standstill. They are like lame turtles, they pull in their legs, heads and tails at the slightest contact and hide inside their shells. How can any spiritual energy emerge from such an attitude? If they by chance encounter an authentic monk and are subjected to a sharp verbal attack, they react like Master Yan’s pet stork, who when the time came to perform, couldn’t even move his neck.

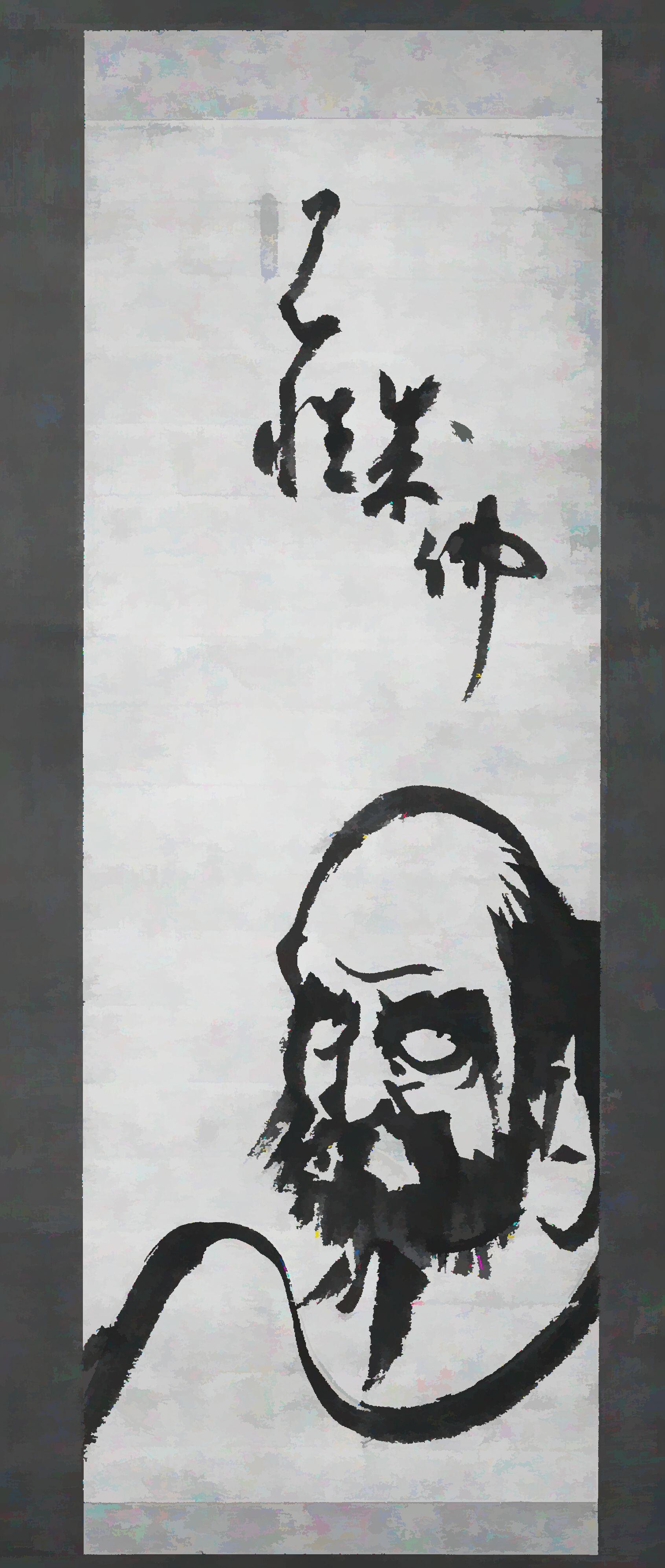

Bodhidharma by Hakuin Ekaku

This passage is from The Essential Teachings of Zen Master Hakuin, translated by Norman Waddell, and is pretty typical of the tone with which Hakuin speaks of his peers who are not on the same Rinzai path. I could take up pages with examples of the dry wit he displays when taking umbrage with the Soto practitioners of his day. He does not take the same tone with the Pure Land Buddhists however, seemingly respecting their perspective. It’s fair to say that his harsh tone is reserved for fellow Zen practitioners alone.

Two things come up for me. First, similar to our current political climate, I’m not surprised that many of his colleagues found it refreshing and appealing to have someone express so much vitriol. My second reflection is to notice how this aspect of Hakuin is in stark contrast to the sixth, and possibly the seventh, precept. The sixth precept is “I take up the way of not discussing faults of others,” and the seventh precept is “I take up the way of not praising myself while abusing others” (Aitken Roshi). Having studied hundreds of pages Hakuin, it’s hard to make the argument that he honored either of these precepts. Keep this in mind as you listen to Rinzai Dharma teachings.

Hakuin The Artist

As mentioned above, Hakuin did not critique Pure Land Buddhism or, in fact, any of the traditional cultural practices of 18th-century Japan. When one looks at his art, one can see appealing images of many folk deities, bodhisattvas, esoteric Shinto deities and other gods and goddesses. His favorite images included Hotei, the fat bodhisattva who wandered around giving out gifts, and Bodhidharma, who sat facing a wall. His art included large, bold calligraphy of essential phrases like Mu, Chu, Fudo, virtue, death and stability to name just a few. Hakuin painted common, ordinary things like dancing foxes, storks, monkeys, pilgrims, blind men and landscapes. His images typically include text, which gives the viewer clues as to the Zen nature of his paintings.

Inka Staff by Hakuin Ekaku

I gather from the textual analysis of Hakuin’s paintings, of which he produced over 3,500 in his lifetime, that his art offered him an opportunity to capture images from ordinary life in a way that allowed him to teach the Dharma. He could refer back to his teachings in subtle ways. For example. He wrote this poem, published in Poison Flowers in a Thicket of Thorns:

Circling the rim of an iron grindstone,

An ant goes round and round without rest.

Like all beings in the six realms of existence,

Born here and dying there without release,

Now becoming a hungry ghost, then an animal,

If you are searching for freedom from suffering,

You must hear the sound of one hand.

In a painting entitled “Ant on a Grindstone,” he wrote the following haiku:

Circling the grindstone,

An ant-tis world’s

Whisper

Hakuin would go on to draw an “Ant on a Grindstone” many times.

There are so many wonderful images in Hakuin’s canon of art and calligraphy. This blog cannot do justice to his wisdom and skill. The takeaway is that not only was Hakuin a rigid taskmaster as a Zen teacher, he was also a skilled artist, who gave away paintings and calligraphy as a way of spreading the Dharma through visual images and texts that pointed toward the way of Zen.

After two full blogs on the life and teachings of Hakuin Ekaku, I can say I’ve only scratched the surface. I’m sure I could write a whole blog on Song of Zazen alone. There are, after all, two books written about this one piece! What I can say to sum it up is that Hakuin was a genius in the conventional sense of the word. His command of textual Zen was outstanding. He was a committed Dharma patriarch, who lived and breathed Dharmic truth, and he shared this with his students and his audience. In this way, Hakuin brought Zen back into fashion in the early 18th Century. As practitioners in his lineage almost 300 years later, I continue to see his stamp on so much of what we do. I am deeply moved by his art and I am grateful that we are able to continue to learn from his wisdom.