Understanding Our Lineage - Pt. 2

In the first part of my investigation of our Rinzai lineage, I traced the direct transmission from my teacher Jun Po Denis Kelly Roshi directly back to Hakuin Ekaku. Read Full Blog. All modern day Rinzai lineages can be traced through Hakuin Ekaku, who was responsible for revitalizing Rinzai Zen in the early 18th century. I’ve always wondered what happened to Rinzai approach that needed to be revitalized, and how did Rinzai get to Japan in the first place? This blog will take a look at how the teachings of Linji Yixuan (the traditional Chinese name of Master Rinzai) made its way to Japan to become the object of Hakuin’s teachings.

Ōtōkan Lineage- Daiō, Daitō, Kanzan

Nanpo Jōmyō (大應國師 / 大応国師 Daiō Kokushi, 1235–1308)

Shūhō Myōchō (大燈国師 Daitō Kokushi, 1282–1337)

Kanzan Egen (無相大師 Musō Daishi, 1277–1360), founder of Myōshin-ji Temple

The term Ōtōkan comes from the “ō” of Daiō, the “tō ” of Daitō, and the “kan” of Kanzan).

In the Tang era of China, roughly the eighth and ninth centuries, there were five houses of Chan (the Chinese precursor of Japanese Zen). These schools were Caodong, Yunmen, Fayan, Guiyang and Linji. Only two of these schools would continue to thrive into the 20th century, Caodong, which is Soto Zen, and Linji, or Rinzai Zen. While not the first exposure to Japan, Myoan Eisai, a Shinto priest, traveled to China in 1168, returning to Japan with Tendai texts. He returned to China in 1186 and studied with Chan Master Kian Esho, a teacher of the Linji house. He received “inka,” or transmission, four years later and returned to Japan. Thus, just as Bodhidharma established Chan in China, Eisai established Rinzai in Japan. However, for reasons beyond this discussion, Eisai returned to his Tendai roots in his later years and did not continue with the Rinzai teachings. He did, however, recognized a formal heir, Ryonen Myozen (1184–1225).

Ryonen Myozen too traveled to China, where he studied for three years before passing away. He traveled with Dogen Kigen who brought Myozen’s ashes back to Japan. Dogen Zenji is well known as the founder of Soto Zen in Japan.

Another source of Rinzai Zen was brought to Japan by Enni Benien, who is also know as Shoichi Kokushi. Enni’s Zen was a blend of Rinzai Zen and Tendai Buddhism.

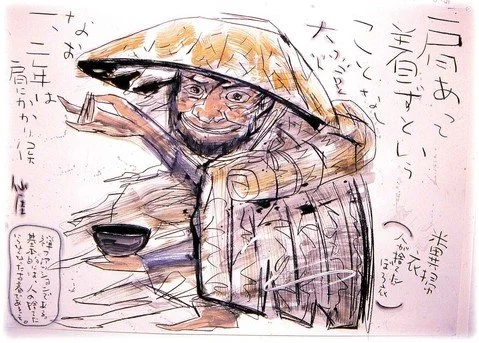

Our lineage was initiated in Japan by Nampo Jomyo (1235–1308), who was a nephew of Enni Benien. He traveled to China as well, where he received inka transmission from Xutang Zhiyu (1185–1269), also known as Kido Chigu. Jomyo was given the posthumous name Daio Kokushi. Jomyo’s most famous proclamation is “my coming today is coming from nowhere. One year hence, my departing will be departing to nowhere.”

Shuho Myocho (1277–1360), who was given the posthumous name Daito Kukusho, was recognized as the heir of Nampo Jomyo after he brought forth the following poem to Jomyo

Having once penetrated the cloud barrier

The living road opens out north, east, south and west

In the evening resting in the morning, roaming, neither host nor guest.

At every step the pure wind rises.

As with many of the Roshis, Shuho Myocho was a talented poet. Another verse:

Sitting in meditaton

One sees people

Crossing and re-crossing the bridge

Just as they are.

Shuho Myocho passed the torch on to Kanzan Egen (1277-1360). Along with Daio Kokushi and Daito Kukusho, our school was know as the Otokan school (“o” from Daio, “to” from Daito, and “kan” from Kanzan). These three masters largely shaped the Rinzai Lineage that Hakuin would pick up in the 18th century.

Little is left of Kanzan Egen’s dharma teachings. One fragment is entitled “Honnu Enjō Butsu,” the Inherently Perfect Buddha. The Inherently Perfect Buddha is our original nature. Kanzan used this concept as a koan to help his students to awakening: “If we all are inherently perfect buddhas, why then have we become ignorant, deluded sentient beings?”

Kanzan Egen built Myoshinji, the temple that is the center of modern day Rinzai Zen. From Kanzan Egen, the lineage is held by a dozen Roshis without much fanfare. The lineage is listed here:

Juō Sōhitsu (1296-1380)

Muin Sōin (1326-1410)

Nippō Shōshun (1367-1448)

Giten Genshō

Sekkō Sōshin (1408–1486) Tōyō Eichō (1428-1504)

Taiga Tankyō (?–1518)

Kōho Genkun (?–1524)

Senshō Zuisho

Ian Chisatsu (1514–1587)

Tōzen Sōshin (1532–1602)

Yōzan Keiyō (1559–1629)

We pick up again in the 17th century with Gudō Tōshoku (1577–1661), who left no written record, however, he is known as a reformer of Rinzai practice. He served as abbot of Myoshinji three times. His disciple Shidō Bunan (1603-1676) was a teacher of Hakuin Ekaku (1685-1768). Gudō received the posthumous title Daien Hokan Kokushi.

Shidō Bunan said: “If you can really get to see your original Mind, you must regard it as if you were raising an infant. In whatever you do such as walking, standing, sitting, lying down, be aware of Mind so that everything is illuminated by it, so that nothing of the seven consciousnesses (vijnana) soils it. If you can keep him [the new born Mind] clear and distinct, it is like an infant growing up becoming equal with the father.”

Master Bunan too was a poet:

There are names,

Such as Buddha, God, or Heavenly Way:

But they all point to the mind

Which is nothingness.

Shidō Bunan had one heir – Dōkyō Etan (1642-1721). Dōkyō Etan is also known as Shoju Rojin “The Old Man of Shoju Hermitage.” Hakuin writes much about him in his autobiography Wild Ivy. He lived a simple life in a small hermitage called Shoju-an. While he published little. We do have his death poem, which is a tradition in Japan:

Hurrying to die,

It’s difficult to find a last word.

If I spoke the wordless word,

I wouldn’t speak at all!

There is not clear evidence that Hakuin Ekaku received inka from Dōkyō Etan, though we do know that Hakuin lived at Shoju-an. Hakuin sees himself as in the Otokan lineage through Gudō Tōshoku. We will discuss Hakuin in a separate blog.